dgavshon

Share this via Facebook

Share this via X

More sharing options

This opinion editorial was co-authored by Daniela Gavshon, Australia Director at Human Rights Watch, and Kyinzom Dhongdue, Advocacy Manager at Amnesty International Australia.

Tibetans around the world mark their National Uprising Day on 10 March, commemorating the 1959 rebellion against the rule of the People’s Republic of China in Tibet. But Tibetans in China won’t be marking it publicly. They continue to suffer widespread violations of their human rights, which have only worsened under President Xi Jinping’s repressive rule.

The fact that the international community rarely hears much news from Tibet anymore is not a coincidence — it is a consequence of China’s increasing efforts to seal off information from the region. There is no independent civil society, nor is there freedom of expression, association, assembly, or religion in Tibet.

The government has stepped up intrusive policing and surveillance as it forcibly assimilates the culturally distinct Tibetans into the Chinese nation. Tibetans must do what they are told — for instance, use Mandarin Chinese instead of Tibetan as a medium of instruction in schools, and relocate en masse from their long-established villages to sometimes hundreds of kilometres away — because any form of questioning government policies can lead to detention, enforced disappearance, and torture.

Many Tibetans — like the family of Kyinzom herself — fled across the Himalayas following the Tibetan Uprising and went into exile. But this option doesn’t exist anymore insofar as the Chinese government severely restricts Tibetans’ access to passports and has effectively sealed off the border to those seeking to cross without permission. Even simply communicating with the outside world — such as calling one’s family in exile — is a dangerous act.

These acts of repression reflect a larger campaign that appears intended to hollow out and erase Tibetans’ unique culture, language, and identity. Yet, as Tibetans suffer without effective recourse, the Chinese government is curating a version of Tibet, much like a theme park, that they want visitors to see. This is why the visit to Tibet by Australia’s ambassador to China, Scott Dewar, in October 2024 was so disappointing. His failure to challenge this mirage was a missed opportunity — especially since it was the first visit of Australia’s ambassador in over a decade.

In the absence of unfettered access, visiting Tibet risks being turned into a stage-managed propaganda exercise. However, a diplomatic visit can also present a valuable opportunity to highlight human rights abuses. Whether this potential is realised depends on what happens during the visit, and what happens after.

When the Sydney Morning Herald covered the Australian ambassador’s visit to Tibet in 2013, the headline read, “Tibet: Australian ambassador pulls no punches on human rights concerns after rare visit”. This time around, however, the Australian government issued no public statement on human rights and the trip slipped largely under the public’s radar. The Australian and international media barely reported on the trip.

The Chinese government, on the other hand, publicised this visit in official media — with the consent of the Australian embassy — portraying it as an educational visit during which the Australian ambassador could learn about “Tibet’s development and prosperity” so he could “introduce the beautiful, prosperous, open and progressive Tibet” to Australians.

Imagine, instead, that the ambassador had immediately issued a press release following the visit or, better yet, addressed the media and named the Tibetan political prisoners such as the disappeared Panchen Lama or the imprisoned monk philosopher Go Sherab Gyatso.

The ambassador could have been a strong voice for Tibetan human rights. But when pressed at Senate Estimates, the Australian government stated that human rights concerns were raised in private. When it comes to human rights violations as grave as those in Tibet, public accountability is essential.

It is not too late. This year, as another Tibetan Uprising Day approaches — and this date falls within Losar, or Tibetan New Year — the Australian government can use this occasion to make its voice heard. A high-profile, public appearance by Ambassador Dewar or Foreign Minister Penny Wong with the Tibetan community in Australia would send a powerful message of solidarity.

But words alone are not enough. Australia should also take concrete action. Following the United States government’s funding freeze on foreign aid, some Tibetan civil society groups in exile are now facing an unprecedented financial crisis. These organisations cannot raise funds inside Tibet due to Chinese government repression. And they cannot easily do so abroad due to the Chinese government’s long arm, weakening their capacity to document abuses and advocate for human rights and provide vital support to their community.

Ultimately, for the human rights situation in Tibet to improve, strong and determined solidarity and action will be needed from countries like Australia.

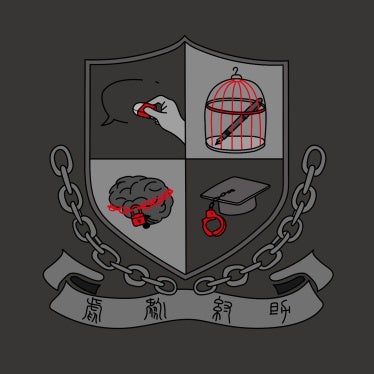

Academic Freedom in Hong Kong Under the National Security Law

China’s Forced Relocation of Rural Tibetans

출처: Human Rights Watch